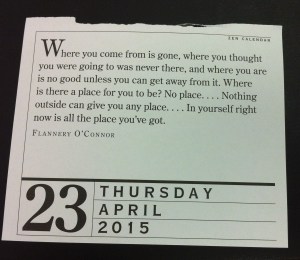

Robert Pirsig’s recent passing has led a lot of people to reflect on Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, which he published in 1974. He acknowledges in his author’s note that the book has nothing to do with “orthodox Zen Buddhism,” but the rest of the book makes it clear that he’s not interested in orthodox Zen Buddhism in the first place. Instead, Pirsig understands Zen as direct, unmediated experience that cannot be expressed in language. In this sense, his book is about Zen, but it’s the kind of Zen that isn’t tied to a particular culture, history, or religion.

For Pirsig, Zen is the romantic counterpart to the rational, logic-driven mindset that he initially favors. Eventually, he concludes that one must embrace and balance the rational and the romantic to achieve Quality, a philosophical ideal in which one finds fulfillment. Zen isn’t the only religion or philosophy Pirsig draws from in developing his idea of Quality, though; Greek philosophy, Hinduism, and the thought of people like Henry David Thoreau also play important roles, even to the point of overshadowing Pirsig’s use of Zen. Yet the connection between Zen and this book remains outsized due to its title and its influence on popular conceptions of Zen in the U.S.

Pirsig didn’t invent the idea that Zen is fundamentally about direct experience, or “being in the moment.” As the UC Berkeley Buddhist Studies scholar Robert Sharf points out in two articles (one on Zen and Japanese nationalism, the other on the idea of experience in Buddhism), D.T. Suzuki popularized this notion, drawing on Romanticism as well as the Kyoto School philosophy of Nishida Kitarō. Suzuki’s version of Zen inspired Eugen Herrigel, the Nazi who wrote Zen in der Kunst des Bogenschiessens, or Zen in the Art of Archery in 1948. Herrigel presented Zen as a kind of practiced effortlessness that underlay archery as well as various other Japanese arts. These ideas, as well as Herrigel’s title, clearly inspired Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (though there were several other Zen in the Art of… titles that came out just before Pirsig’s title, such as Ray Bradbury’s Zen in the Art of Writing in 1973).

Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance marked a shift to “Zen and the Art of…” titles, replacing the previous “Zen in the Art of…” titles. Ironically, Pirsig’s philosophy suggests that his title should have been “Zen in the Art of…” which would have underscored the importance of direct experience in motorcycle maintenance, a skill that to Pirsig symbolized of the rational approach to life. Regardless, Pirsig’s title paved the way for a slew of Zen and the Art of… books, from Zen and the Art of Making a Living to my personal favorite, Zen and the Art of Cooking Beer-Can Chicken. These titles may seem superficial and incidental, but they have significantly shaped perceptions of Zen in American popular culture. Not only is Zen inextricably tied to art (however one may define it), it can also be associated with absolutely anything. These titles remove any historical or cultural specificity from Zen Buddhism to make Zen a transcultural, ephemeral experience. This ties in very closely to how Pirsig presents Zen in the body of the book as well.

At the same time, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance has sparked its many readers’ interest in Zen, Buddhism in general, and comparative religions. The book’s creative structure, which combined road trip memoir, autobiography, and philosophical treatise, echoes its eclectic contents. While it may not cohere as much as a traditional narrative, it provokes deeper reflection and challenges readers to make their own meaning from Pirsig’s journeys. I think this is why the book has left a mark on so many people, and even steered some into the academic study of religion.

I was honored to discuss Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance earlier this week on PRI’s The World. I hope it’s of interest!