Time is the reason I haven’t been able to update more frequently, so it seemed appropriate to resurrect this site by looking at the $13.99 Zen Page-a-Day® Calendar from Workman Publishing, based in New York. The box promises “surprising sayings, koans, parables & haiku for 2015” as well as a mini meditation primer in the first part of January. Its packaging displays a close-up photo of a rock garden, a pile of three round stones on a bed of neatly raked sand. The quotation on the back of the box reveals much about how the calendar’s creators understand Zen:

“The only people who get anyplace interesting are the people who get lost.” — Henry David Thoreau.

Thoreau was interested in Buddhism and translated the Lotus Sūtra into English for the first time, but even more than that his attitude toward Buddhism and Hinduism set the stage for popular understandings of these traditions in the U.S. (thanks to Jeff Wilson for the correction — it was Elizabeth Palmer Peabody who translated the Lotus Sūtra into English) He did not convert to Buddhism, but explored Buddhism alongside Christianity, Greek religion, and Hinduism, seeking the deeper truths of existence he saw as underlying each. This approach has spread in the centuries since, as evidenced by the Zen calendar’s broad definition of Zen. While Thoreau had a connection to Buddhism (if not Zen specifically), there are plenty of figures quoted in the calendar who didn’t. Take, for example, Mark Twain (Tuesday, July 28: “A thing long expected takes the form of the unexpected when at last it comes”), Pablo Neruda (Wednesday, May 20: “When did the honeysuckle first sense its own perfume? When did smoke learn how to fly?”), and the generic “Spanish proverb (Tuesday, January 6: “It is not the same thing to talk of bulls as to be in the bullring”).

The calendar quotes from many Buddhist figures, such as Ruth Denison, Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, and the Dalai Lama, and does include several Zen masters, as well, among them Mazu, Dōgen, and Hakuin. However, to be considered Zen a quotation just has to be pithy and vaguely mystical, evoking the literary genres of the kōan and haiku. This understanding of Zen goes back to the image developed by people like D.T. Suzuki: if everything is Zen, anything is Zen.

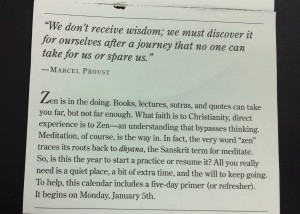

D.T. Suzuki’s influence is also apparent in the introduction and mini meditation primer that presents a basic form of meditation over the week of January 5-9. The introduction proclaims that Zen is about meditation and direct experience (hence the Proust quotation), which could come straight from Suzuki’s writings about the timeless essence of Zen. As with other aspects of modern Buddhism, these notions aren’t necessarily wrong or inauthentic from an academic perspective, but they are recent, which is to say that the idea of timelessness is not itself timeless.

The primer prescribes meditation focused on the breath, which isn’t unique to Zen (or Buddhism), but is part of Zen meditation practice. The author shows some familiarity with Japanese Zen in referring to zafu and zabuton cushions, and in alluding to the concept that seated meditation is enlightenment. On the last page, the author even encourages readers to seek out a sangha, or Buddhist community, for group practice. Considering the usual emphasis on solitary practice in the home or office in Zen products, I found this suggestion surprising. As a whole, however, this calendar falls into the category of made-in-China desktop Zen products meant to provide calm and contemplation during a hectic workday.